Bible Recap Reading Plan 2024 PDF: A Comprehensive Guide

Embark on a transformative journey! This guide explores the 2024 Bible Recap plan, offering insights into its structure, translations, and community engagement opportunities.

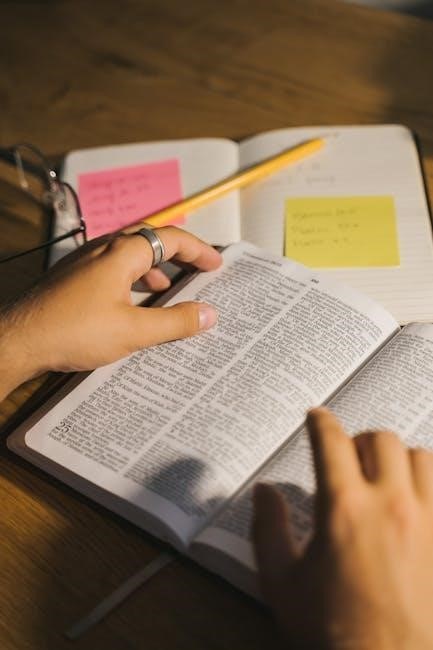

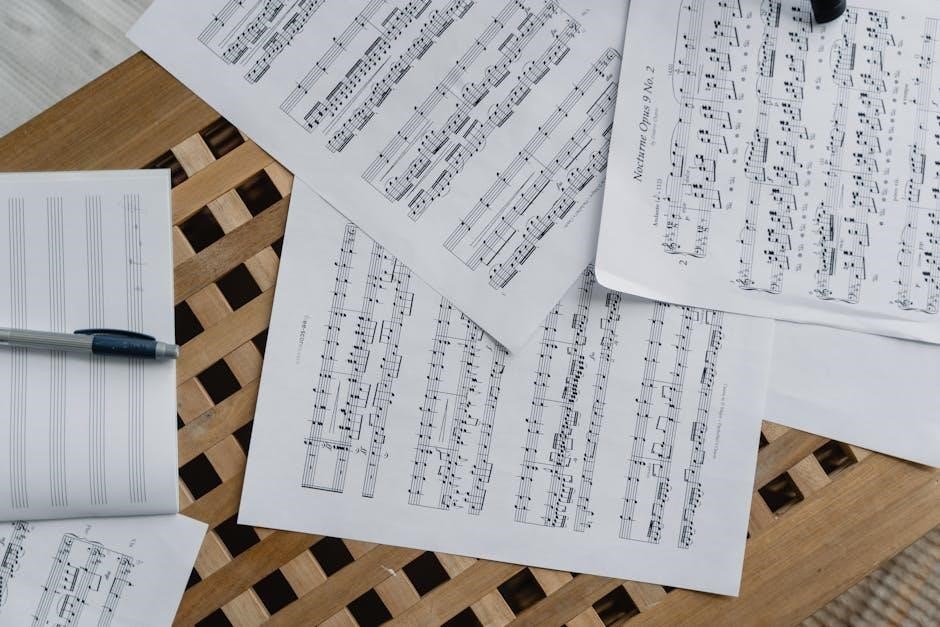

The Bible Recap is a guided reading plan designed to help individuals read the entire Bible in one year. It’s gained significant traction, particularly with the release of its 2024 version, offering a structured approach to scripture. This isn’t simply about completing the Bible, but about understanding its overarching narrative and core themes.

The plan emphasizes connecting with the Word of God and focusing on Jesus Christ as the central figure throughout scripture. It acknowledges the Bible’s role as divine revelation while encouraging thoughtful interpretation within its historical and literary context. The 2024 plan, often accessed via a convenient PDF, aims to make this journey accessible to a wider audience, fostering both individual and communal engagement with the Bible.

What is the Bible Recap Plan?

The Bible Recap Plan is a daily reading schedule that systematically guides readers through the entire Bible over 365 days. It breaks down the biblical text into manageable daily portions, fostering consistent engagement with scripture. Unlike reading the Bible cover-to-cover, the plan often employs a chronological or thematic approach, revealing the interconnectedness of biblical stories and teachings.

The core principle is to understand the Bible as a unified narrative pointing towards Jesus Christ. The 2024 plan, frequently utilized in its PDF format, provides a clear pathway for individuals to immerse themselves in God’s Word, encouraging reflection and spiritual growth. It’s designed for both new and seasoned Bible readers seeking a structured reading experience.

The Popularity of the 2024 Plan

The 2024 Bible Recap Plan has gained significant traction due to its accessibility and community focus. Its popularity stems from providing a structured approach to Bible reading, overcoming the challenge of knowing where to begin. The readily available PDF format enhances convenience, allowing users to access the plan on various devices.

Furthermore, the plan’s emphasis on understanding the Bible’s overarching narrative, directing readers towards Jesus, resonates with many. Online forums and social media groups dedicated to the plan foster a sense of shared journey and accountability. This communal aspect amplifies motivation and encourages deeper engagement with scripture, contributing to its widespread appeal.

Understanding the 2024 Plan Structure

Delve into the plan’s design! It features a daily reading breakdown, offering choices between chronological and traditional approaches for a personalized experience.

Daily Reading Breakdown

The 2024 plan meticulously divides the Bible into manageable daily portions. Each day typically includes readings from multiple books, blending Old and New Testament passages. This structure aims to provide a comprehensive overview of scripture throughout the year. The length of daily readings varies, accommodating different reading paces and schedules.

The plan isn’t simply about quantity; it’s about consistent engagement. It encourages readers to not just read the text, but to reflect upon its meaning and application to their lives. The daily format fosters a habit of regular scripture intake, promoting spiritual growth and a deeper understanding of God’s Word. It’s designed to be accessible, even for those new to consistent Bible reading.

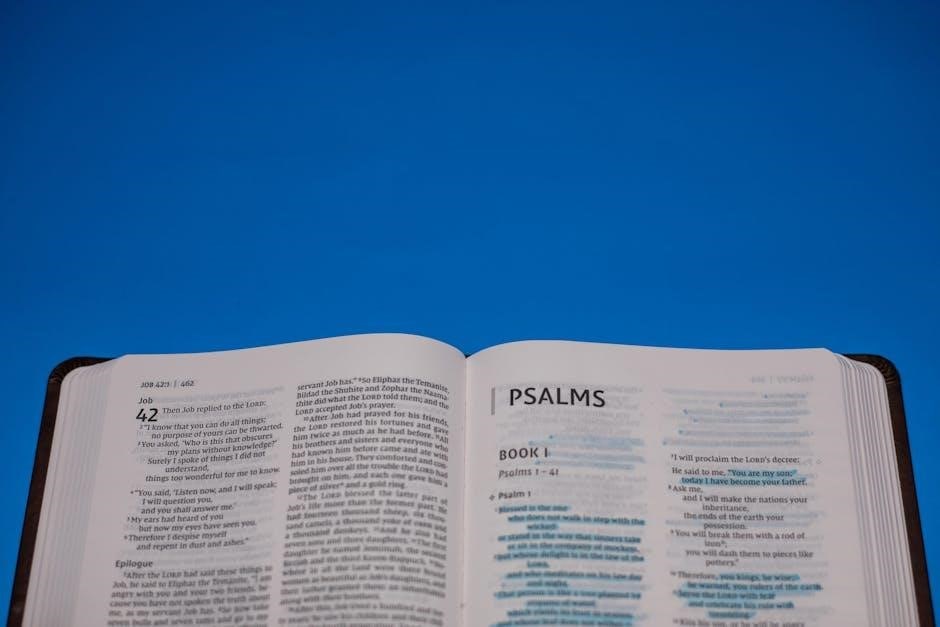

Chronological vs. Traditional Reading

The Bible Recap plan primarily employs a chronological reading order. Unlike traditional plans that follow the biblical book sequence, this approach arranges readings based on the estimated historical timeline of events. This reveals a compelling narrative flow, showcasing how God’s story unfolds progressively.

Traditional reading, while familiar, can sometimes feel disjointed, jumping between genres and historical periods. The chronological method aims to provide context, illuminating how different biblical events relate to one another. It helps readers grasp the overarching narrative arc of scripture, fostering a richer understanding of God’s redemptive plan. However, some prefer the book-by-book approach for focused study.

The Role of the PDF Format

The 2024 Bible Recap plan’s PDF format offers unparalleled accessibility and convenience. It allows users to download the entire reading schedule for offline access, eliminating reliance on internet connectivity. This is ideal for travel or areas with limited service.

Furthermore, PDFs are universally compatible across devices – smartphones, tablets, and computers – ensuring a seamless reading experience. The digital format facilitates features like search functionality, enabling quick location of specific passages or themes. Many PDF readers also support note-taking, allowing for personal reflection and study directly within the document. Printing is also an option, catering to those who prefer a physical copy.

Key Bible Translations for the Recap Plan

Choosing the right translation enhances understanding! NASB prioritizes accuracy, NIV focuses on readability, and ESV strikes a balance, aiding your 2024 Bible Recap journey.

NASB (New American Standard Bible) ⏤ Accuracy Focus

For the precision-minded reader, the New American Standard Bible (NASB) stands out. Renowned for its literal translation approach, the NASB meticulously aims to convey the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts with utmost fidelity. This makes it an excellent choice for in-depth Bible study and those desiring a close rendering of the source material during the 2024 Bible Recap.

While potentially less fluid than some other versions, the NASB’s commitment to accuracy minimizes interpretive bias. It’s favored by scholars and those who want to grapple directly with the nuances of the biblical languages, even in English. Utilizing the NASB alongside the Recap plan can deepen your understanding of the scriptures’ original intent.

NIV (New International Version) ⸺ Readability Focus

The New International Version (NIV) balances accuracy with clear, contemporary English. This makes it a popular choice for a broad audience, including those new to Bible reading or seeking a readily understandable translation for the 2024 Bible Recap. The NIV prioritizes conveying the meaning of the original texts in a way that resonates with modern readers, avoiding archaic language while remaining faithful to the scripture.

Its smooth readability doesn’t compromise essential theological precision. The NIV strikes a harmonious balance, offering accessibility without sacrificing depth. For those prioritizing comprehension and a natural reading experience, the NIV is an excellent companion throughout your daily reading journey.

ESV (English Standard Version) ⏤ Balance of Accuracy & Readability

The English Standard Version (ESV) aims for a “word-for-word” equivalence with the original biblical languages, while still maintaining readability for contemporary English speakers. This makes it a strong contender for those using the 2024 Bible Recap who desire both precision and comprehension. The ESV avoids paraphrasing, striving to present the text as closely as possible to its original form.

However, unlike more literal translations, the ESV employs stylistic choices to ensure a natural and flowing reading experience. It’s a favored choice for serious study and devotional reading, offering a reliable and accessible pathway through the scriptures.

Core Biblical Themes Encountered in the Plan

Discover profound truths! The 2024 plan highlights central themes like God’s unwavering love, finding refuge in Him, and the foundational creation narrative.

The Importance of Love (1 Corinthians 13)

Central to the faith, 1 Corinthians 13 eloquently defines love as the most essential virtue. The chapter emphasizes that even possessing extraordinary gifts – speaking in tongues or exhibiting prophetic abilities – is meaningless without genuine love.

Paul illustrates this with powerful imagery, comparing actions devoid of love to “a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal.” True love, as described, is patient, kind, and doesn’t envy or boast. It’s not proud, rude, or self-seeking.

This passage challenges readers to examine their motivations and actions, ensuring love guides their interactions. The 2024 Bible Recap plan’s inclusion of this chapter serves as a vital reminder of love’s paramount importance in a believer’s life and relationship with God and others.

Finding Refuge in God (Psalm 91)

A powerful declaration of faith, Psalm 91 portrays God as a secure refuge and fortress for those who dwell in His presence. It assures believers that they will rest in the shadow of the Almighty, finding safety and protection from dangers both seen and unseen.

The psalm speaks of deliverance from pestilence, snare of the fowler, and the terror of the night. Declaring God as “my refuge and my fortress,” it emphasizes complete trust in His unwavering care.

Within the 2024 Bible Recap plan, encountering Psalm 91 offers a comforting reminder of God’s constant protection and provision. It encourages readers to cultivate a deeper reliance on Him, especially during times of uncertainty and fear, solidifying faith through His promises.

The Creation Narrative (Genesis 1)

The foundational account of all existence, Genesis 1 details God’s deliberate and powerful creation of the heavens and the earth. From formless void to a beautifully ordered cosmos, each day witnesses God speaking life into being – light, sky, land, vegetation, and ultimately, humankind.

The narrative emphasizes God’s sovereignty and intentionality. He doesn’t merely shape creation, but speaks it into existence, demonstrating His absolute power and authority.

As part of the 2024 Bible Recap, revisiting Genesis 1 reminds us of God’s creative power and establishes a framework for understanding His relationship with creation and humanity. It’s a powerful starting point for appreciating the entirety of scripture.

Navigating Difficult Biblical Passages

Unlocking scripture’s complexities! This section addresses challenging texts – Genesis 3, baptism, and the Lord’s Prayer – for deeper understanding within the plan.

Addressing Questions About Genesis 3 (The Serpent)

Delving into the narrative of Genesis 3, many readers ponder the serpent’s ability to speak. Why wasn’t Adam and Eve surprised by a talking animal? The text reveals the serpent was “more crafty than any other beast of the field,” suggesting a deceptive intelligence.

This wasn’t simply an animal conversation; it was a spiritual attack. The serpent, understood in later scripture as Satan, exploited Eve’s curiosity and doubt. The Bible Recap plan encourages examining the context – the perfect environment of Eden and the direct command from God – to grasp the gravity of the serpent’s deception.

Understanding this passage requires recognizing the spiritual warfare at play, not merely a literal animal encounter. It’s a pivotal moment illustrating the entrance of sin and the need for redemption.

Understanding Baptism – Water vs. Spirit

A frequent question arises: Is water baptism essential, especially considering Jesus wasn’t recorded as water-baptizing the twelve apostles? The Bible Recap plan guides readers to differentiate between water baptism and baptism of the Holy Spirit. While John the Baptist performed water baptisms as a sign of repentance, Jesus emphasized a deeper, spiritual immersion.

The New Testament highlights the baptism of the Holy Spirit as the defining act for believers, signifying entrance into a new covenant. Water baptism serves as an outward expression of an inward reality – a public declaration of faith following spiritual conversion.

The plan encourages studying the context of baptism throughout scripture to understand its evolving significance.

Interpreting the Lord’s Prayer

The Lord’s Prayer, a cornerstone of Christian faith, often prompts questions about its true meaning. The Bible Recap plan encourages a deeper examination, cautioning against superficial understanding. Jesus warned against “hypocritical” prayer, focused on outward display rather than genuine connection with God.

The prayer isn’t merely a recitation, but a model for authentic communication with the Father. Each phrase—from adoration (“Our Father”) to petition (“Deliver us from evil”)—reveals layers of theological depth.

The plan prompts readers to consider the cultural context and original language, avoiding interpretations that prioritize performance over heartfelt devotion. It’s a guide to truly praying the prayer, not just saying it.

Utilizing the 2024 PDF Effectively

Maximize your reading experience! The 2024 PDF offers convenient access, search capabilities, note-taking features, and flexible printing options for focused study.

Downloading and Accessing the PDF

Securing your 2024 Bible Recap PDF is straightforward. Typically, the PDF is available for download directly from the Bible Recap’s official website or through associated promotional channels. Ensure you are downloading from a trusted source to avoid any security risks. Once downloaded, the PDF can be accessed on a variety of devices – computers, tablets, and smartphones – allowing for reading flexibility.

Most PDF readers, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader (free to download), will be required to open and view the document. Consider saving the file to a readily accessible location on your device for quick and easy access each day. Digital access streamlines your daily reading, eliminating the need for physical copies and promoting consistent engagement with the plan.

Features of the Digital PDF (Search, Notes)

The digital 2024 Bible Recap PDF offers enhanced functionality beyond a traditional printed version. A key feature is the search capability, allowing you to quickly locate specific verses, themes, or keywords within the entire reading plan. This is invaluable for revisiting passages or exploring related content.

Furthermore, most PDF readers enable you to add personal notes directly within the document. Utilize this feature to record insights, reflections, or questions that arise during your daily readings. These notes become a personalized study aid, enriching your understanding and fostering deeper engagement with scripture. The interactive nature of the digital PDF truly elevates the reading experience.

Printing Options and Considerations

While the digital PDF is highly recommended, printing the 2024 Bible Recap plan is certainly an option. However, consider the document’s length – printing the entire plan can consume significant paper and ink. Opt for printing only the current month or week to conserve resources.

When printing, experiment with different settings like double-sided printing and grayscale to further reduce costs. Ensure your printer is adequately supplied with ink and paper before starting a large print job. Remember that a physical copy lacks the search and note-taking features of the digital version, so weigh the benefits before committing to a full print.

Connecting with the Bible Recap Community

Join fellow readers! Engage in online forums, social media discussions, and connect with pastors and small groups for shared support and insights.

Online Forums and Discussion Groups

Dive deeper into the daily readings! Numerous online platforms foster vibrant discussions surrounding the Bible Recap plan. These forums provide a space to ask questions, share personal reflections, and gain diverse perspectives on scripture. Participants often dissect challenging passages, offering interpretations and support.

Dedicated discussion groups, often hosted on platforms like Facebook or dedicated websites, allow for focused conversations on specific themes or books within the reading plan. These communities are invaluable for those seeking clarification, encouragement, or simply a shared experience. Engaging with others enhances understanding and strengthens faith, transforming a solitary reading experience into a collective journey.

Social Media Engagement

Connect and share your Bible Recap journey! Social media platforms have become integral to the Bible Recap experience. Users actively share daily insights, favorite verses, and personal reflections using dedicated hashtags, fostering a sense of community. Platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook are buzzing with discussions and encouragement.

Many participants utilize social media to ask questions, receive prayer requests, and celebrate milestones within the reading plan. Following the official Bible Recap accounts provides access to daily reminders, supplemental content, and opportunities to engage with the wider community. This digital connection amplifies the impact of the plan, creating a supportive network for readers worldwide.

The Role of Pastors and Small Groups

Enhance your understanding through guided discussion! Pastors and small group leaders play a vital role in deepening engagement with the Bible Recap plan. They can facilitate discussions, provide contextual insights, and address challenging passages encountered during daily readings. Utilizing the plan within a small group setting fosters accountability and encourages shared learning.

Pastors can integrate the Bible Recap readings into their sermons, connecting the daily scripture with broader theological themes. Small groups offer a safe space to explore personal applications of the text and wrestle with difficult questions. This collaborative approach transforms individual reading into a communal experience, strengthening faith and building relationships.

Theological Considerations While Reading

Focus on Christ! Remember the Bible directs us to Jesus, understanding context and interpretation while recognizing it as the inspired Word of God.

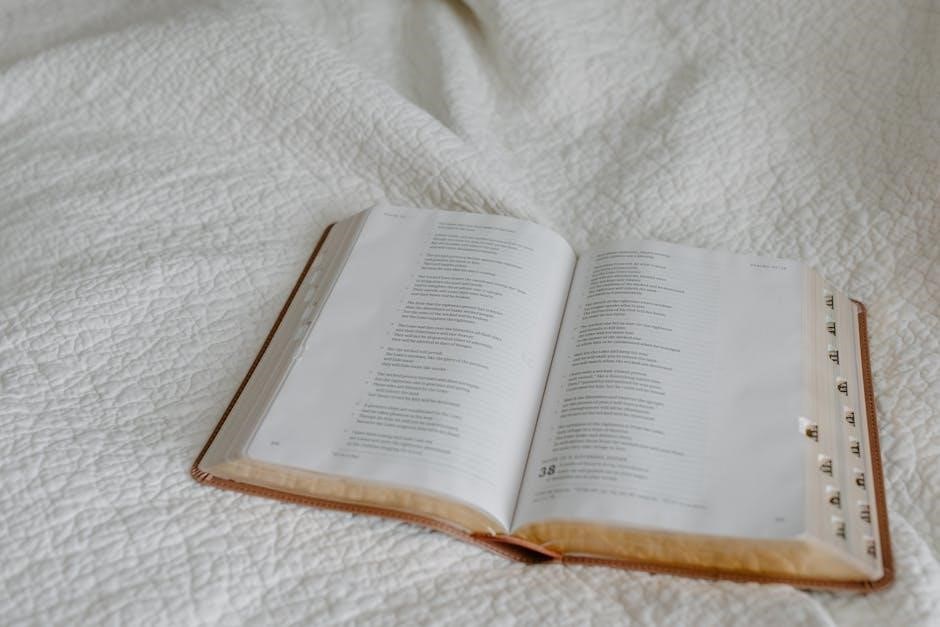

The Bible as the Word of God

Understanding Divine Revelation: Recognizing the Bible as the Word of God is foundational to the Recap plan. It’s not merely a collection of stories, but a divinely inspired text revealing God’s character, plan, and relationship with humanity.

This perspective shapes how we approach each passage, seeking not just historical or literary understanding, but also God’s intended message for our lives. While acknowledging human authorship, faith affirms God’s overarching guidance in its composition.

This belief doesn’t negate critical thinking; rather, it informs it, prompting us to interpret Scripture with reverence and a desire to understand God’s truth. The Bible consistently points towards Jesus Christ, the ultimate revelation of God.

Focusing on Jesus Christ

Christocentric Reading: The 2024 Bible Recap plan, like all faithful Bible study, should ultimately lead us to a deeper understanding of Jesus Christ. The entire biblical narrative—from Genesis to Revelation—testifies to His person and work.

Recognizing Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies and the central figure of God’s redemptive plan transforms our reading experience; Every story, law, and poem finds its ultimate meaning in Him.

As you progress through the plan, actively seek connections between passages and Christ. How does this text foreshadow His coming? How does it reveal His character? The Bible always directs us to Jesus, the Word made flesh.

Understanding Context and Interpretation

Navigating Scripture: The 2024 Bible Recap plan benefits greatly from careful contextual interpretation. Don’t isolate verses; consider the surrounding text, historical setting, and author’s intended audience. Understanding the cultural nuances of biblical times is crucial.

Recognize literary genres – poetry, narrative, law, prophecy – each requiring a different approach. Avoid imposing modern perspectives onto ancient texts. Seek to understand what the text meant to the original audience before applying it to your life.

Utilize study resources, but always prioritize the Bible itself. Remember, sound interpretation honors God’s Word and avoids twisting Scripture to fit pre-conceived notions.

Resources to Supplement Your Reading

Enhance your study! Explore Bible commentaries, study Bibles, and online tools for deeper understanding, enriching your 2024 Bible Recap experience.

Bible Commentaries

Delving Deeper with Commentary: Bible commentaries provide invaluable context and insights, enriching your understanding of the scriptures encountered within the 2024 Bible Recap plan. They offer historical background, explain difficult passages, and illuminate the original meaning of the text. Consider commentaries from various theological perspectives to broaden your comprehension.

Recommended Resources: The Matthew Henry Commentary is a classic, offering comprehensive verse-by-verse explanations. John Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible provides detailed analysis. For a more modern approach, explore the New American Commentary series. Utilizing commentaries alongside the plan fosters a richer, more informed reading experience, helping you grasp the nuances of God’s Word.

Study Bibles

Enhance Your Recap Experience: Study Bibles are essential companions for the 2024 Bible Recap plan, offering a wealth of supplementary information directly within the biblical text. They include features like book introductions, character studies, maps, charts, and cross-references, all designed to deepen your understanding and engagement with scripture.

Popular Choices: The ESV Study Bible is highly regarded for its scholarly notes and comprehensive resources. The NIV Study Bible provides accessible explanations and practical applications. The MacArthur Study Bible offers a distinct theological perspective. A well-chosen study bible will significantly enrich your daily reading, providing context and fostering a more profound connection with God’s Word during your recap journey.

Online Bible Tools and Websites

Digital Resources for Deeper Study: Numerous online tools complement the 2024 Bible Recap plan, offering convenient access to scripture and insightful resources. Bible Gateway (biblegateway.com) provides multiple translations, commentaries, and reading plans. Blue Letter Bible (blueletterbible.org) excels in detailed lexical studies and original language tools.

Enhance Comprehension: Websites like BibleProject (bibleproject.com) offer visually engaging videos exploring biblical themes and narratives. YouVersion (youversion.com) provides interactive reading plans, devotionals, and community features. Utilizing these digital resources alongside the PDF plan can unlock deeper understanding, facilitate personal reflection, and enrich your overall Bible Recap experience.